By: Karl Nadolsky, DO, FACE

Published July 2020

The loudest voices expressing the most extreme recommendations often get the most attention. So in the world of nutrition, especially dietary efforts for weight loss, the variety of popular fad diets frequently deliberated and utilized seem to cause public discourse. Often is the case that fad diets are popularized through media and sometimes seemingly cult-like tribalism rather than through discussing nuances of scientific evidence. Nonetheless, the science gets debated among experts, leading to confusion in media reports and most certainly among the target audience of the community.

According to the Oxford dictionary, “fad” is defined as “an intense and widely shared enthusiasm for something, especially one that is short-lived and without basis in the object's qualities.” A fad diet is generally popular for a brief or long time period without being a standard dietary recommendation per se. Fad diets often promise inflated and/or quick results such as significant weight loss and/or health benefits. They also often are touted as the only way, requiring little effort or based upon pseudoscience. Unfortunately, such promotion may and frequently does hinder education about the overall diet and personalized variations/preferences along with other critical lifestyle changes necessary for sustainable health benefits.

For whatever reason, many people, including celebrities, become self-proclaimed experts in diet and nutrition because of the potentially lucrative business and extend beyond real expertise. On the other hand, nutritional scientists and physicians have studied some fad diets and elucidated likely benefits and risks, providing potential for dietary prescription and use of some concepts in those dietary plans.

Red Flags

Cleveland Clinic suggests that fad diets tend to have:

- Recommendations that promise a quick fix.

- Claims that sound too good to be true.

- Simplistic conclusions drawn from a complex study.

- Recommendations based on a single study.

- Dramatic statements that are refuted by reputable scientific organizations.

- Lists of "good" and "bad" foods.

- Recommendations made to help sell a product.

- Recommendations based on studies published without peer review.

- Recommendations from studies that ignore differences among individuals or groups.

- Elimination of one or more of the five food groups (fruits, vegetables, grains, protein foods, and dairy).

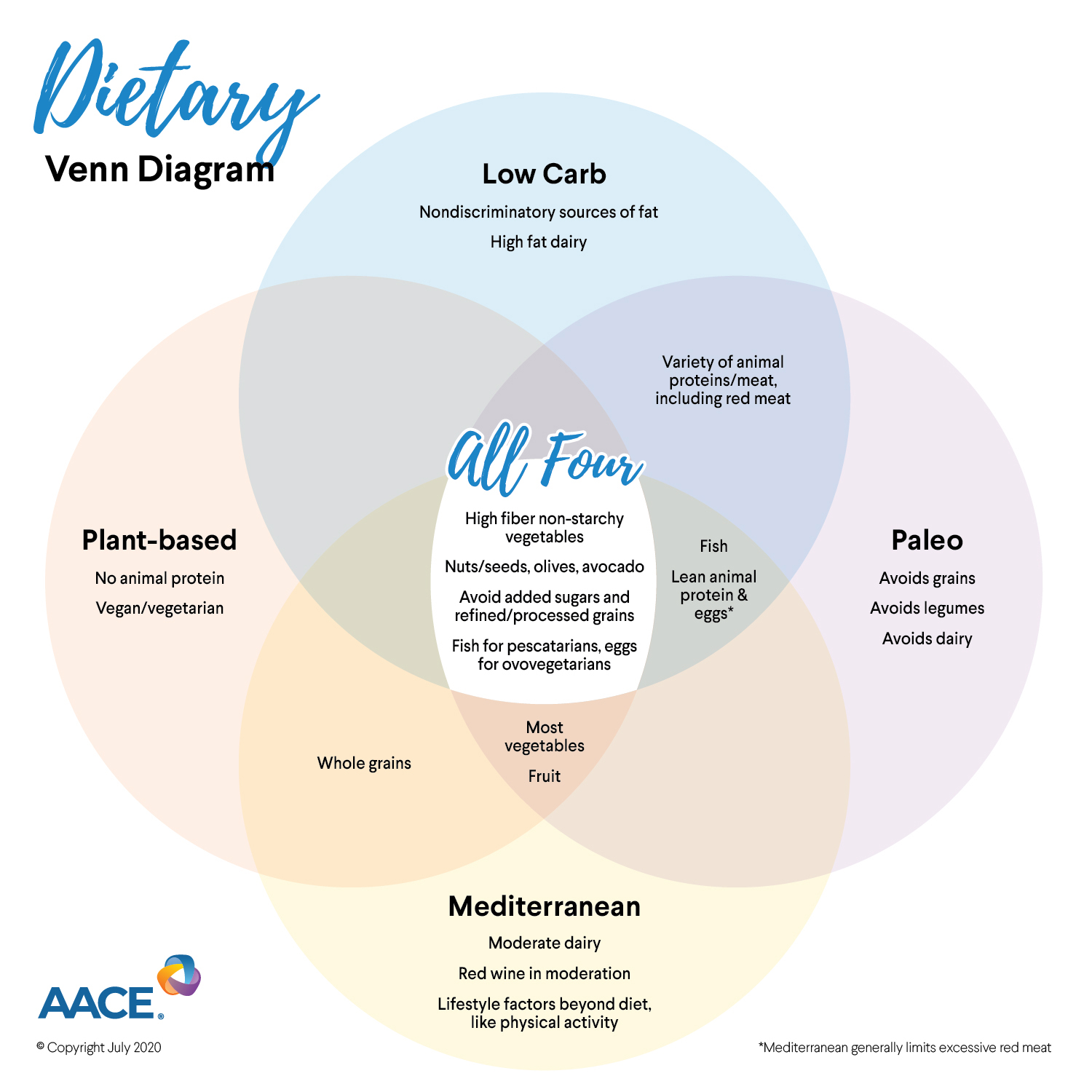

Weight loss. Patients with obesity should be prescribed a reduced-energy food plan to restrict caloric intake while following some basic patterns of healthy eating. Guidelines recommend reducing intake by 500 to 750 calories per day (estimating targets of 1,200 to 1,500 calories daily for women or 1,500 to 1,800 calories for men) or eating patterns with restrictions to create an energy deficit and weight loss. Dietary patterns or fads which have been studied and shown to be beneficial include macronutrient (protein, carbohydrate and fat) manipulation like carbohydrate restriction (low-carb diets with as little as 20 grams of carbohydrate daily) or lower glycemic index/load diets, low-fat diets or fat restriction, plant-based or vegetarian to vegan plans, high-protein diets (often >25% of calories from protein), Mediterranean diet, paleo or caveman diet or utilization of meal replacements. Recently, meal timing has become popular and fairly well studied. Periods of prolonged fasting, popularly coined “intermittent fasting or alternate-day fasting” among others, have proven to be a viable method to achieve energy restriction, weight loss and health benefits. “Blood-type” diets have no scientific evidence despite some popularity. While studies investigating genetic variability for specific dietary response have been mixed and currently are not recommended, this concept has led to emergence of research into nutrient-gene interactions relevant to obesity.

Historically, perhaps the two most common types of popular dietary plans have been variations of low-fat or low-carbohydrate diets. Low-fat diets have been popularized by Dr. Dean Ornish in recent years, while Dr. Atkins led the low-carbohydrate craze, which has evolved into several variations including low carb with high protein, low carb with high fat, very low carb and protein with high fat or ketogenic, and often incorporated into popular dietary patterns such as paleolithic or even fasting plans.

The optimal macronutrient distribution for weight loss has been frequently debated and remains controversial but ultimately comes down to adherence to the energy deficit when compared in trials (Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers or Zone diets). It is most likely that one approach will not suit all patients and an analysis of many popular diets that included 48 unique trials revealed nearly identical weight loss results at 12 months. Replacing empty dietary sources of calories with nutrient-dense whole foods should be a focus of medical nutrition therapy and anyone working on improving his or her diet for weight loss and health.

Low carbohydrate, Atkins, low carb–high fat, keto. Starchy, refined and processed available carbohydrates and sugary foods or drinks are frequent sources of excess energy intake in many people’s diets; thus, carbohydrate restriction generally works well to reduce energy intake. Scientifically, there has been a proposed carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity with proponents claiming that low carb–like Atkins or ketogenic diets reduce insulin and thus cause fat-burning and improved metabolism. Similarly, achieving states of ketosis with high-fat diets has been proposed to improve metabolism. These concepts have not been confirmed in well-done trials and have essentially been debunked. Regardless, ketogenic diets may improve satiety (the feeling of being full) while carbohydrate restriction can be a valuable tool when improving one’s nutritional plan. Starch, sugar, grains, beans/legumes, starchy fruits and even starchy vegetables are generally cut out of the diet while very low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets are more restrictive, including lower protein but allowing higher fat. Ketogenic diets restrict carbohydrates to less than 25–50 grams daily to primarily use fat or ketones as fuel. These diets were originally used to treat epilepsy and today are very popular, although they must be cautiously approached. First of all, many people find this degree of restriction very difficult to adhere to and are most often not truly ketogenic but may still benefit from carbohydrate restriction. Problems arise when individuals try to increase dietary fat from undesirable sources which have been touted to be healthy like butter, coconut oil, fatty meats or other added oils; this can lead to side effects and may have concerning effects in some people on their metabolic and cardiovascular health. Combining carbohydrate restriction with eating patterns like whole-food/plant-based or Mediterranean diets known to have healthy foods is a preferable approach.

Low fat. Low-fat diets like Ornish and many plant-based or vegetarian variations historically were thought to make sense but unfortunately have been misconstrued to give many a false sense of security. Their recommendations have been inappropriately blamed for the explosion of low-fat but high-sugar/-carbohydrate foods and snacks perhaps contributing to obesity struggles.

Reducing or restricting sources of dietary fat leads to an energy deficit and weight loss like low-carb diets but is also confounded by variable and poor adherence. Analyses of trials comparing low-fat and a variety of higher-fat dietary interventions have shown minimal to no advantage either way and benefit is dependent upon the intensity of the interventions regardless of which diet. Controlled feeding trials looking at low-carbohydrate/high-fat diets compared to high-carbohydrate/low-fat diets with protein and calorie consumption held constant by providing food to subjects also show minimal difference but slightly favor the low-fat diets in terms of energy expenditure and weight difference.

High protein. Several studies have suggested that diets higher in protein (>25%–30% of daily calories) may improve satiety, resulting in lower overall caloric intake plus a slight metabolic advantage and comparative weight loss. Dietary protein is also beneficial for maintaining muscle during weight loss, though high protein consumption should be cautiously personalized in patients with kidney disease. High protein consumption in those without kidney disease, even very high levels in trained athletes, has not been shown to be detrimental. Additionally, a study using high-protein low-energy meal replacements for people with obesity and prediabetes did not reveal any changes in kidney function.

Carnivore. By descriptive definition, this dietary fad excludes food other than animal meat or products and naturally is extremely high in protein while obviously very low in carbohydrate and variable in fat. It is the meat-lover’s opposite response to a vegan diet. On the surface this sounds potentially very hazardous and is certainly suboptimal to exclude plant-based foods with known health benefits like vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts/seeds, etc. However, as with any extremely restrictive diet, weight loss will occur due to markedly lower energy intake and obviously cuts out any “empty” calories from sugary drinks/foods, baked goods, sweets, and other processed/refined starchy carbohydrates. The health risks of primary concern include adverse cardiometabolic changes like cholesterol pattern and cardiovascular risk. Lean meat and fatty fish would be a preferable strategy with this diet though it remains far from recommended. What about our evolutionary history? Well, we are omnivores; thus we can be flexible!

Paleo. Paleolithic or caveman diets include food patterns based on the premise of our pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer ancestors including vegetables, fruit and animal meats/products. Loren Cordain popularized the paleo diet with several books based upon an article in the New England Journal of Medicine titled "Paleolithic Nutrition.” This plan eliminates processed/refined grains but also many foods with known health benefits including dairy and beans/legumes, but ironically many advocates often permit processed meat products like bacon. Overall, the concepts of this approach can markedly improve the quality of one’s diet and generally its quantity, resulting in weight loss due to caloric restriction and health benefits, but caution must be taken to avoid inclusion of unhealthy or caloric food just because it is “paleo” like high-fat meats. On the other hand, there are potentially healthy food options such as dairy and legumes/pulses that may be excluded for people adhering to a strictly paleo plan. Additionally, many strict paleo dietary recommendations include animal meat that is only “wild” or “grass-fed” which may have marginal relative health benefits but significantly increased cost. This is especially true when compared to healthful alternatives with similar health goals, such as salmon with significant omega-3 fat rather than fatty beef from grass-fed cows.

Plant-based, vegetarian, vegan. The incorporation of larger portions of low-energy-dense foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and legumes/pulses, provides essential fiber and phytonutrients while maintaining satiety and restricting energy intake. Vegetarian dietary patterns generally exclude meat products but span a broad spectrum to include even the raw vegan diet of only raw vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds, legumes, and sprouted grains. Trials comparing vegetarian diets to non-vegetarian diets do result in weight loss but include vegan, lacto- (inclusion of dairy) and ovo-vegetarian (inclusion of eggs) varieties.

Vegan diets exclude all animal products including eggs, dairy and even honey or anything made with gelatin. While incorporating very healthy whole foods from plants emphasizing nuts/seeds, legumes, vegetables and fruits, the vegan diet is very restrictive and puts one at risk of nutrient deficiencies and suboptimal protein intake.

Perhaps an ideal compromise is a flexitarian diet that focuses on plant-based efforts that incorporate more whole-food plants like vegetables, fruits, legumes/pulses and some whole grains without completely eliminating animal products. Versions of a flexitarian diet include the Nordic diet (whole foods like plants and seafood without complete restriction of land animals) and pescatarian diet (vegetarian diet including fish).

Intermittent fasting or alternate-day fasting. There are a variety of ways to incorporate spells of energy restriction interspaced by habitual energy intake to create an energy deficit for weight loss in hopes of improving adherence. Time patterns of prolonged fasting, popularly coined intermittent fasting or alternate-day fasting among others, have demonstrated potential to achieve energy restriction, weight loss and health benefits. A small trial that compared continuous versus intermittent calorie restriction (controlled for macronutrients protein, carbohydrates and fat) resulted in similar weight loss and subjective appetite ratings without differences in metabolic rate, exercise efficiency or overall appetite-regulating hormone changes. A 1-year trial that compared 2 days weekly of 400/600 daily calories (women/men, respectively) to an equally reduced daily diet showed similar weight loss (8 kg versus 9 kg), cardiometabolic marker improvements and minimal weight regain (1.1 kg versus 0.4 kg, respectively) but higher hunger scores in the intermittent fasting group. This strategy appears to have similar weight and sugar benefits for those with obesity complicated by type-2 diabetes. Many enjoy time-restricted feeding patterns, often delaying breakfast while making sure dinner is finished early. On the other hand, a new small but well-controlled trial showed better metabolism with earlier meals than later meals; perhaps keeping the feeding window earlier in the day could be preferred if tolerable. While this strategy may work for some, it may not be ideal for others.

Dietary quality. While caloric or energy quantity matters, quality is important for health benefits with or without fat loss.

Mediterranean diet. Mediterranean diets are generally characterized by a pattern of vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts/seeds, olive oil, and fish while limiting fatty meat/dairy and avoiding refined grains or added sugar. The Mediterranean diet has been associated with cardiometabolic benefits along with weight loss and improved cardiovascular outcomes. This dietary pattern has been recognized as the top recommended diet by experts in US News & World Report. Observation that those living in the Mediterranean Sea vicinity have better health and longer lives than other western countries led to evaluation of their lifestyle including dietary habits. That said, there are various Mediterranean geographies and not one perfectly defined. While trials that added components such as nuts or olive oil have provided some of the best scientific evidence for health benefits (cardiovascular risk reduction + fat loss), the overall lifestyle pattern is emphasized, even including wine in moderation in addition to family meals and physical activity.

Meal replacements. Very-low-calorie diets (VLCDs, etc).

Non-nutritive sweeteners. While not a fad diet, per se, there has been great controversy and mixed data regarding use of artificial sweeteners or non-nutritive sweeteners, primarily in beverages. Many fads or popular trends include the exclusion of these artificially sweetened beverages. Unfortunately, this has led many people to choose sugar-sweetened beverages, resulting in the adverse effects of excess calories from sugar in the form of high-fructose corn syrup and sucrose. The consumption of caloric or sugar-sweetened beverages is best avoided, as they do not increase satiety and only increase calories consumed. Replacing sugar-sweetened beverages with zero-calorie drinks or water has shown benefit despite observational concerns about non-nutritive sweeteners and their potential differences.

Fads To Pretty Much Ignore

Anything promoting detoxification. It’s not unreasonable to fast briefly before starting a diet with quality components like vegetables and fruits, but this is not technically detoxifying anything, and too often these dietary plans come with the commercialization of supplements without proven benefit and potentially unknown harms. The liver does the work of actual detoxification, so it is much more advisable to improve the quality of eating habits, perhaps incorporating some of the beneficial aspects noted above.

The alkaline diet. Also known as the alkaline-ash diet and the alkaline-acid diet, an alkaline diet requires elimination of meat, dairy, sweets, caffeine, alcohol, artificial and processed foods, and more consumption of fresh fruits and veggies, nuts and seeds. This diet certainly has positive points, relying heavily on fresh produce and other healthy, satisfying foods while eliminating processed fare, which in itself may spur weight loss. But your body is incredibly efficient at keeping your pH levels where they need to be, so cutting out these foods really won't affect your body's pH. Also, there is no research proving that pH affects your weight in the first place. The bottom line: the alkaline diet is strict, complicated and bans foods that can have a place in a healthy eating plan, such as meat, dairy, and alcohol.

Blood-type diet. There is no scientific evidence or strong plausibility that this approach has value but was developed and promoted by a naturopathic physician and gained some widespread acceptance. Peter D'Adamo, the naturopath behind the blood-type diet, suggests that its merit is based on the notion that the foods you eat react chemically with your blood type. For example, on the diet, those with type-O blood are to eat lean meats, vegetables, and fruits, and avoid wheat and dairy. Meanwhile, type-A dieters go vegetarian, and those with type-B blood are supposed to avoid chicken, corn, wheat, tomatoes, peanuts and sesame seeds. However, it has not been shown that your blood type affects weight loss. Also, depending on your blood type, the diet can be extremely restrictive.

Cabbage soup and grapefruit diets. Nutrient-dense low-calorie vegetables and fruits are a good basis for many diets, but generally it is not a good idea to restrict to just these foods as they don’t provide all the required nutrients critical for healthy weight/fat loss.

hCG diet. While there is no evidence that hCG helps with weight loss and dietary adherence, since the hCG diet is a very-low-calorie (500 calories daily) diet, you will lose weight if you adhere to its extreme energy restriction. hCG injections are indicated for fertility issues in women and men but are not FDA-approved for weight loss with good reason.

Bullet-proof coffee. Without going beyond the scope of this article, it is appropriately advised to avoid drinking butter and medium-chain triglyceride oil with coffee despite the efforts of those profiting off this trend.

Concluding Thoughts And Recommendations

Overall, a dietary pattern generally needs to be an energy-restricted plan, at least for those struggling with obesity and related medical problems, that also improves sources of food in both healthful and individualized-preference patterns. Many of the fad diets actually have more in common than they have differences despite sometimes appearing polarizing. Keeping personal preferences and culture in mind, here are some basic tips to individualize dietary improvements.

- Cut out sugar-sweetened beverages.

- Cut down on eating out.

- Increase whole-food, plant-based carbohydrate components of your diet to include vegetables, legumes/pulses and fruit in place of refined/processed starchy or sugary carbohydrates, including many snack foods and baked goods.

- Increase whole-food, plant-based fat components of your diet to include nuts/seeds, olives, avocado and fish in place of refined/processed oils/butters, including many snack foods and baked goods.

- Cut down on high-fat animal products in favor of leaner protein sources.

- Consider your own “fad diet” like a plant-based, lower carb, paleolithic approach with Mediterranean-type food sources while possibly replacing some meals with protein shakes and perhaps even using a time-restricted or intermittent-fasting feeding pattern.

Common themes and individualization

- Intermittent-fasting plans can be implemented to any of the dietary-pattern plans

- Meal-replacement plans can be incorporated into any of the dietary-pattern plans

Combination of dietary plans can help personalize dietary plans for individual preferences.